Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression

Arthroscopic subacromial decompression may be a difficult technique to learn; good equipment therefore is essential. Everything must be done under direct vision, and hence control of bleeding is an essential requirement. This may be achieved in one of two ways.

- Increase of intrabursal fluid pressure: this increases postoperative swelling, however.

- Coagulation diathermy: Initially, use of diathermy was difficult because the inflow fluid had to be changed from saline to either water or glycine. However, commercially available point source diathermy probes are available, and these do not require change of fluid and can be used in the presence of saline.

Equipment

An arthroscopic pump is most helpful during arthroscopic subacromial decompression—preferably one that allows variability of flow and pressure. By the use of a pump, the pressure can be kept just low enough to maintain adequate visualization and hence reduce postoperative swelling and tissue edema. This usually means keeping the intra-articular pressure just above arterial pressure. A power shaver is essential, and the actual type is of critical importance. Many shavers have been developed for use in the knee and are in no way adequate for acromioplasty. On the undersurface of the acromion is a very odd, rubbery connective tissue at the insertion of the coracoacromial ligament. This can be difficult to get through and can block most shavers. The best shaver can only be found by trial and error, and the decision must be made whether to use disposable blades or reusable. With some systems, two different types of blade must be used. First, a soft tissue resector to remove the coracoacromial ligament and the soft tissue on the undersurface of the acromion down to bone, and second, a bony burr. However, various acromio-plasty/notchplasty blades are available that can remove both bone and soft tissue with an adequately high-speed shaver. This is important if disposables are being used, because it halves the price.

Position of Patient

The patient is placed in the lateral position with 10 lb of traction applied.

Technique

A standard glenohumeral arthroscopy is performed via the posterior portal. This enables assessment of the undersurface of the rotator cuff. The scope is then withdrawn and inserted into the subacromial bursa. The bursa itself is then carefully inspected (see Ch. 10).

First the bursal surface of the rotator cuff is inspected to confirm the presence of an impingement lesion. This is an area of roughening and inflammatory change on the bursal surface of the rotator cuff, with a corresponding "kissing" lesion on the undersurface of the acromion. The undersurface of the acromion and coracoacromial ligament insertion may be inflamed and rough. The presence of these findings confirms the diagnosis of impingement. Hence the surgeon can proceed to acromioplasty. If a three-portal technique is to be used, then an outflow portal may be established anteriorly by the usual railroading technique and by pushing the sharp obturator anteriorly and inferiorly to the acromion.

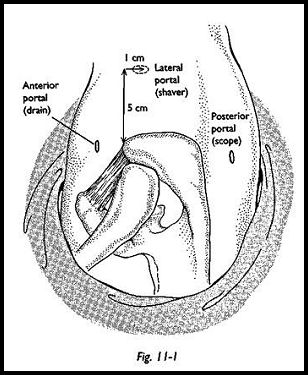

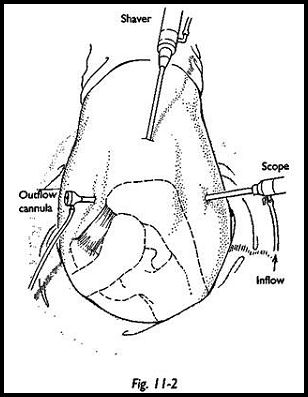

The third portal (shaver portal) is a direct lateral access point. The anterior edge of the acromion is identified, and a line running parallel to this down the arm is drawn 0.5 cm from the lateral edge of the acromion and 1 cm posterior, which is the ideal entry point for the power shaver (Fig. 11-1). A 5-mm stab incision is made here, and the shaver is aimed toward the surface of the lateral acromion (Fig. 11-2). Again, a feeling of "give" is experienced as the shaver enters the bursa. The circumflex nerve is not endangered by this approach, because although this runs at approximately 5 cm from the lateral point of the acromion, the shaver is aimed always more proximally and never deep, directly onto the humerus.

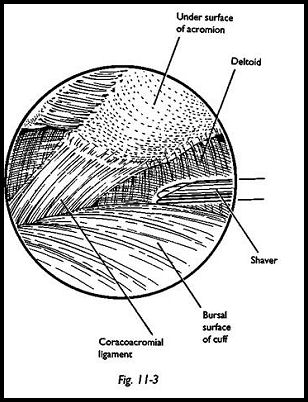

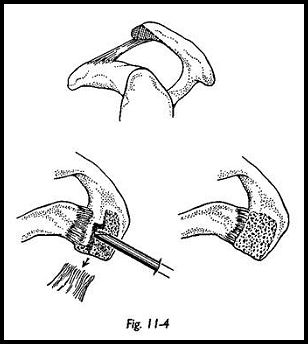

Some initial soft tissue resection may be required to gain adequate visualization, but the undersurface of the acromion is inspected (Fig. 11-3). By direct vision and feel, any hooking or spurs on the undersurface of the acromion may be assessed. The attachment of the coracoacromial ligament to the anterior aspect of the acromion is inspected. It is usually easier to start burring into the bone immediately posterior to the attachment of the coracoacromial ligament, having broken through into cancellous bone. The shaver is then moved forward to disinsert the coracoacromial ligament and push it off the anterior border of the acromion. This delineates the exact bony margins of the acromion. By shaving further medially and palpating the joint externally, one can visualize the acromioclavicular joint (Fig. 11-4). All bone lying anterior to the acromioclavicular joint is excised down to its full depth. This is best done starting laterally and then working medially. The main bleeding point that can give rise to operative difficulty lies in the medial border of the coracoacromial ligament, and hence much work is done laterally before proceeding too far medially.

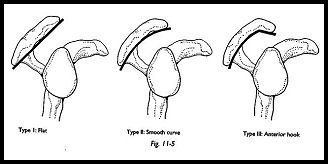

After removal of the whole thickness of the acromion anteriorly, the anterior edge of the acromion is then shaped and angled posteriorly to leave the undersurface of the acromion as a straight line, that is, removing the hooking of the acromion and leaving a straight undersurface (Fig. 11-5).

Assessing the Adequacy of Bone Removal

To some extent, assessing the adequacy of bone removal depends on experience, but assessment can be made by several different techniques. First, the diameter of the shaver tip is known, and this can be used to assess absolute measurement of depth and width of bone excised. The width of the resection can be verified by exactly delineating the origin of the coracoacromial ligament by working from lateral to medial. If the acromioclavicular joint is reached, then by definition, this must be the full width of the acromion. The undersurface of the outer end of the clavicle is also inspected for inferior osteophytosis, and these should be removed if also causing impingement. To assess whether the undersurface of the acromion is left as a straight line now that the hook has been removed, a probe may be passed through the anterior drainage portal to confirm that this configuration has been achieved—the "butcher's block" method. At the end of the procedure, the bursa should be thoroughly irrigated to remove all possible traces of small bone dust. The incidence of new bone formation is greater using a burr than using an awl-type blade, because the bone debris is removed immediately. The scope, drain, and shaver are removed, and at this stage, the shoulder may be swollen. No sutures are used for closure of the wound, but the irrigation fluid is allowed to leak out. A padded dressing is applied over the wound and the arm is placed in a sling

Postoperative Management

Initially, the swelling may be quite tense, with movements limited by swelling, but the amount of swelling is related to (1) the length of the procedure and (2) the irrigation pressure and flow; hence, the pressure should be kept to a minimum to control the bleeding and to provide adequate visualization. Intra-musculature pressure returns to baseline within a very short time at the end of the procedure.1 The arm is held in a sling for comfort, elbow flexion exercises are started immediately, and pendulum exercises are started the next morning. The procedure may be done on an outpatient/day case basis. Patients are encouraged to move the arm from the earliest opportunity and is told that no harm can be done by moving the shoulder, even though it may hurt. They are asked to discard the sling as soon as possible. In practice, the majority of patients get rid of the sling within the first week. They are shown a mobilizing exercise regimen and are seen again at 2 weeks, when they have a reasonable range of movement, up to and above shoulder height, but repetitive movements above shoulder height are still uncomfortable at that stage. Patients are told that an 80-percent improvement will occur by 3 months after surgery, but improvement will continue for several months after that. As with most forms of shoulder surgery, the prediction of pain is extremely variable. The majority of patients have very little pain, but a few have considerable pain.

Reference

1. Ogilvie-Harris D J, Boynton E: Arthroscopic acromioplasty. Extravasation of fluid into the deltoid muscle. Arthroscopy 6:52, 1990

Suggested Readings

Conn RA, Cofield RH, Byer ED, Linstromberg JW: Interscaling block. Anaesthesia for shouldersurgery. Clin Orthop 216:94-8, 1987 Copeland SA, Williamson DM: Suturing arthroscopy wounds: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]70:145, 1988 Ellman H, Gartsman GM: Arthroscopic Shoulder Surgery and Related Procedures. Lea & Febiger,

Philadelphia, 1993 Flatow EL, Cordasco FA, Bigliani LU: Arthroscopic resection of the outer end of the clavicle from a superior approach. A critical, quantitative radiographic assessment of bone removal. Arthroscopy 8:55, 1992

Gartsman M et al: Arthroscopic acromio-clavicular joint resection. An anatomic study. Am J SportsMed 19:2, 1991 Resch H: Arthroscopy of the Shoulder. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1992