Shoulder Instability Biomechanics

Lennard Funk

The shoulder is potentially one of the most unstable joints of the body, with very little bony stability or containment and has been likened to a golf ball on a golf tee. There is a fine balance between the mobility to perform athletic activities and stability required to power and stabilise the arm. The shoulder is not simply a joint but rather a complex and therefore known as the ‘shoulder complex’. It is comprises thirty muscles, six ligaments, four major bones and tendons. The shoulder complex starts proximal to the scapula and the complex can be likened to a dog balancing a ball on its nose whilst standing on a pivot platform (see figure).

The shoulder is stabilised by both static and dynamic stabilisers, which work in synchrony to maintain shoulder stability in performing the extreme activities required by the shoulder in sports and heavy manual work.

The static stabilisers comprise the vacuum effect, labrum, capsule and bones. The dynamic stabilisers are the muscles and proprioceptive effects.

STATIC STABILISERS

1. Vacuum Effect

There are three mechanisms providing the vacuum effect. These are:

1. Intracapsular pressure - This is normally a negative pressure within the shoulder joint. Perforation of the joint breaks that pressure thus leading to slight excess in mobility of the joint. A slightly negative intra-articular pressure exists in a normal shoulder aids in centring the humeral head. It has been shown that less force is required to translate a humeral head anteriorly or posteriorly in shoulders that have been vented to the atmosphere.

2. Suction effect - The glenoid labrum acts on the humeral head like a plunger.

3. Adhesion cohesion - when two wet surfaces, such as the humeral head and glenoid, come into contact with each other this creates an adhesion-cohesion bond, which provides stability to the glenohumeral articulation.

2. Bony Geometry

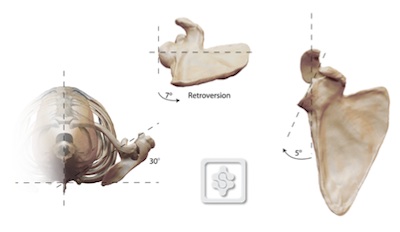

The glenoid is normally retroverted 7 degrees to the scapula, but the scapula is anteverted 30 degrees to the coronal plane of the body, thus preventing posterior instability. Glenoid version may be an important component of the bony stability in the shoulder and an example of where this is pathological is in patients who develop posterior instability with glenoid dysplasia.

Glenoid Dysplasia:

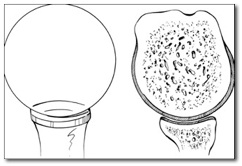

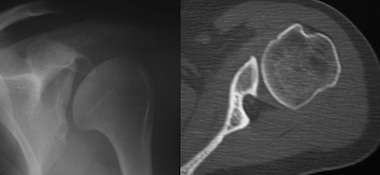

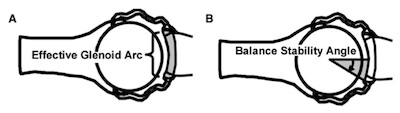

The amount of glenoid and humeral head bone available to articulate is also important for the bony stability. The effective glenoid arc (gray area in image below) is defined as the area of the glenoid articular surface available for humeral head compression. This can be calculated using the balance stability angle, which is the angle between the centre of the glenoid and the end of the effective glenoid arc in any direction. This is 18° in the anterior direction. Any bony loss reducing the glenoid arc and balance stability angle can lead to instability.

3. Glenoid Labrum

The glenoid labrum is a fibrocartilaginous ridge shaped rim circumscribing the glenoid. It is the primary attachment for the glenohumeral ligaments and gives rise to the long head of biceps superiorly. The glenoid labrum is approximately 9mm thick, thus serves to deepen the glenoid socket. It conforms perfectly to the curvature of the humeral head and increases glenoid depth by 50%.

The labrum has also been compared to a chuck block, such as that against the wheel of a vehicle preventing abnormal translation.

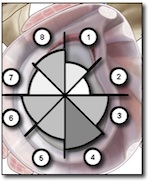

The glenoid labrum is also strongest posterosuperiorly and anteroinferiorly which are the common areas of labral tears. Posterosuperiorly being SLAP tears and anteroinferiorly the common Bankart tears (Huber and Putz 1994; C. Smith UCL PhD 2010).

4. Capsule

The glenohumeral joint capsule is thickened to form specific glenohumeral ligaments, the most significant of these is the inferior glenohumeral ligament. This forms a band anteriorly and posteriorly, the anterior band being the thicker of the two. These bands provide stability in internal and external rotation, with the anterior band tightening in external rotation and abduction, whilst the posterior tightens in internal rotation. Together they form a hammock inferiorly resisting inferior translation.

DYNAMIC STABILISERS

1. Proprioception

It has been shown that the glenohumeral joint capsule has numerous mechanoreceptors particularly within the anterior and inferior capsule (Jerosch 1997 and Gohlke 1998). In abduction and external rotation these mechanoreceptors are most likely activated as the humeral head comes into contact with the capsule sending a signal to the stabilising muscles of the shoulder providing containment and stability of the humeral head.2. Muscles

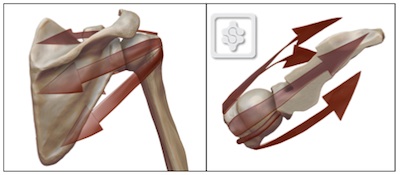

The muscles of the shoulder are divided into the scapular muscles which transfer energy generated from the trunk and lower limbs into the arm and the rotator cuff muscles which are the fine tuning muscles maintaining the centre of rotation of the humeral head.The rotator cuff muscles provide significant stability to the shoulder joint, almost hugging the joint to the glenoid. Wuelker et al. showed that a 50% decrease in the rotator cuff muscle forces resulted in nearly a 50% increase in anterior displacement of the humeral head in response to external loading at all glenohumeral joint positions.

The subscapularis muscle provides anterior stability when the arm is in neutral but less so as the arm comes into abduction (Turkel et al. 1984).

The infraspinatus and Teres minor act together to reduce the strain on the antero-inferior glenohumeral ligament in abduction and external rotation. They are therefore known as the “hamstrings” of the glenohumeral joint (Cain et al. 1987).

The scapular muscles transfer the potential energy of the trunk to kinetic energy in the shoulder. The kinetic train is a concept describing the transfer of energy from the trunk to the shoulder and arm (Kibler 1990). The scapula is a key link in the kinetic chain between the trunk and the shoulder.

Kibler's kinetic chain and the overhead athlete:

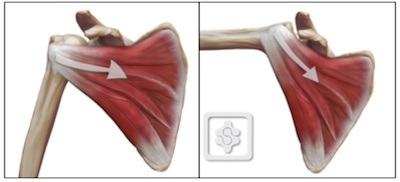

The scapular muscles provide a stable base for shoulder movement. The key force couples in scapular mobility and stability are the lower trapezius and serratus anterior muscles, but the upper trapezius levator scapulae, rhomboids and pectoralis minor also provide stability and mobility. Repetitive or chronic scapular protraction may result in excessive strain, and ultimately, insufficiency in the anterior band of the IGHL (Weiser et al. 1999).

SUMMARY

As can be seen above the shoulder is stabilised by numerous structures both acting dynamically and statically through phases of movement allowing the extreme activities that the arm is capable of performing. Damage to one structure is most likely to have a knock on effect to the others and treatment should be directed accordingly.

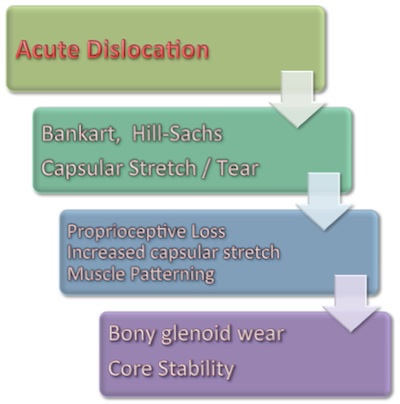

It is also fair to conclude that no single structure provides stability to the shoulder and a dislocation of the shoulder will result in injury to multiple stabilisers of the shoulder. An acute traumatic dislocation is likely to lead to a Bankart tear, a Hill Sachs lesion as well as a capsular stretch or possible tear of the capsule. With progressive instability there will be more proprioceptive loss from the capsule with increased capsular stretch. This proprioceptive disorganisation will lead to muscle patterning problems, repeated continued dislocations and subluxations and can progress to bony glenoid wear and affect core stability and the full kinetic chain. It would therefore make sense that early treatment and stabilisation would be advantageous based on the principles above.