Clinical evaluation and treatment algorithm of the unstable AC-joint

Lennard Funk

ISES 2013

Why should we bother to treat ACJ injuries? It is clear from recent published review articles that there is no difference between the outcomes of non-operative or operative treatment. In fact, surgical treatment is associated with a higher complication rate than non-operative [Ceccarelli et al. J Orthopaed Traumatol, 2008]!

… Why bother?

Background

Acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) injuries range from a ‘sprain’ of the ACJ ligaments to complete disruption of the coracoclavicular ligaments and ACJ ligaments with significant displacement of the joint. There does not appear to be a clear association between the degree of displacement and on-going symptoms and disability. The traditional classification systems (Allman-Tossy and Rockwood) are pathological classifications and there is no Level 1 evidence relating the classification systems to treatment algorithms or outcomes(1).Most surgeons use radiographs as for classifying ACJ dislocations, but this is an unreliable method for determining a pathological classification (2). MRI scans may be more beneficial (3), but as mentioned above the classification system may have no relevance to management decision-making. Cox (AJSM, 1981)(4) showed that a large proportion of ACJ injuries remained symptomatic at 6 months post-injury (36% of Grade 1, 48% of Grade 2 and 69% of Grade 3 injuries). Also, 30% of overhead athletes are unable to continue at the same level of sport (5). In contact athletes, many are able to return to sport but struggle with many of the strength and overhead training exercises required to keep them at high level sport.

Ceccarelli et al. (6) reviewed the literature on the evidence for management of Grade 3 dislocations and concluded: “From the literature evaluation, clinical results seem to be comparable between the operative and the conservative treatments, but complications are more evident in the surgery group.”

Therefore, other than high-level overhead athletes, there is little information on which patients benefit from surgery. It is also unclear as to when to perform surgery. Below is my approach to the diagnosis, clinical assessment and treatment algorithm for ACJ injuries.

Clinical Assessment

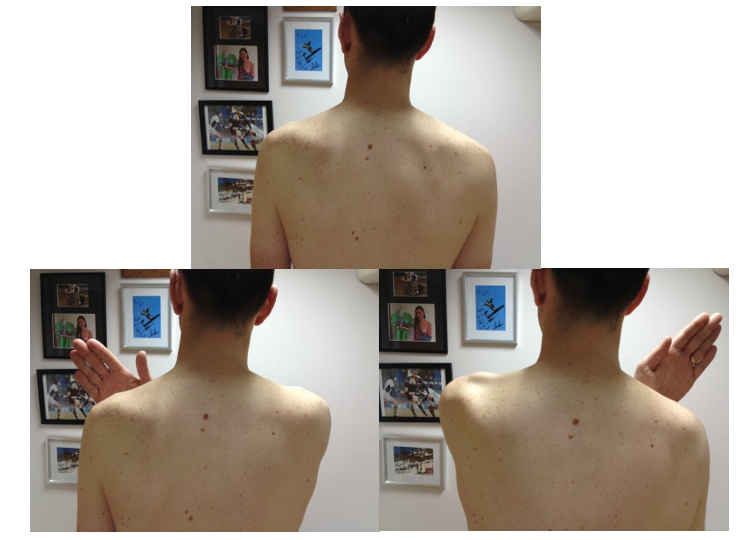

The mechanism of injury for ACJ is typically a fall onto the ‘point’ of the shoulder. The scapula is forced inferiorly by the impact, relatively displacing the clavicle superiorly. The AC ligaments and coracoclavicular ligaments are sequentially torn, with damage to the ACJ, disruption of the delto-trapezial fascia or trapezius muscle.A complete ACJ dislocation (Grade 3-5) is obvious, with a very typical deformity (Figure 1). As the clavicle overrides the acromion it may not allow full scapula excursion during arm elevation. This leads to a variable limitation in full elevation (Figure 2)

| Figure 1: Right sided ACJ dislocation | Figure 2: Limited elevation due to scapula malposition |

|

|

Other dislocations/subluxations are less obvious (These are Grade 2 – 3 injuries). They can clinically be diagnosed by asking the patient to adduct their arm across their chest. This manoeuvre accentuates the injury, displacing the clavicle superiorly and posteriorly (Figure 3).

The lateral clavicle should also be assessed for both vertical and horizontal laxity and compared to the opposite (normal) side. This is done by direct manual palpation. Often excess horizontal laxity is indicative of a significant Grade 2 injury and suggests instability without true dislocation.

Figure 3 – Unstable left ACJ accentuated on cross-chest-adduction

Office ultrasound is useful for dynamically imaging ACJ instability. By pressing on the mid-clavicle any excess mobility of the lateral clavicle can be dynamically seen on ultrasound and displacement measured.

Figure 4 - Video of ACJ instability on dynamic ultrasound

Investigations

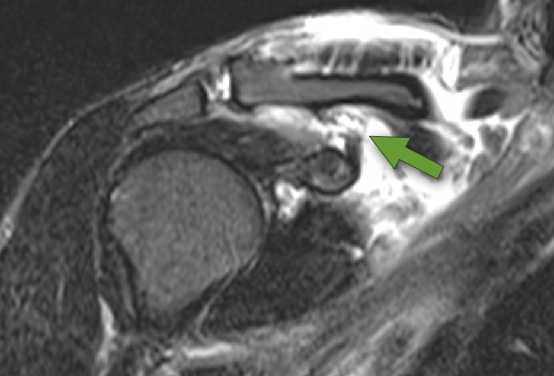

Radiographs are essential. The Zanca view is probably the best view for imaging the ACJ. This is performed 15 degrees cephalad in the A-P plane. However it has not shown to have good inter- or intra-observer reliability. An axillary view has been proposed for posterior displacement, but this also has poor reliability. Weight-bearing views have not been proven to have good reliability either. CT scan is the best form of imaging to appreciate the static bony displacement, however clinical assessment is probably just as reliable. MRI can be useful to assess the soft tissue damage.

Figure 5 - Zanca VIew

Figure 6 - MRI (Arrow showing torn CCL)

Treatment Algorithm

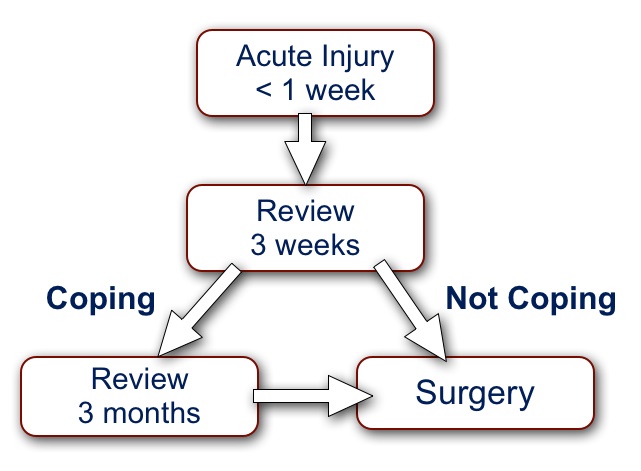

Bearing in mind the considerations gleaned from the published ‘evidence base’, I very rarely perform any acute ACJ stabilisation surgery.

Considerations for surgery:

- Most people with ACJ injuries can cope, unless overhead or high demand athlete

- The long-term outcomes are similar with or without surgery

- Traditional techniques carry a failure rate of approximately 20%

- Acute injury (< 1week):

- Assess and diagnose.

- Sling and analgesia and arrange to review in 3 weeks.

- Surgery if: Clearly in agony with clavicle button-holed through trapezius; Neurovascular injury; Open injury

- 3 week review:

- Settling and improving – continue symptomatic management and gradually reintroduce sports and manual activities. Arrange review at 3 months.

- Not coping – offer early surgical stabilisation

- 3 month review:

- Returned to sports and little symptoms - discharge

- Not coping – offer surgical stabilisation

References:

- Rockwood CA, Green DP, Bucholtz RW. Rockwood and Greens Fractures in Adults. 3rd ed. 1991.

- Ng CY, Smith E, Funk L. Reliability of the traditional classification systems for acromioclavicular joint injuries by radiography. Shoulder & Elbow. 2012 Mar 26;4(4).

- Nemec U, Oberleitner G, Nemec SF, Gruber M, Weber M, Czerny C, et al. MRI versus radiography of acromioclavicular joint dislocation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011 Oct;197(4):968–73.

- Cox JS. The fate of the acromioclavicular joint in athletic injuries. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1981 Jan;9(1):50–3.

- Rangger C, Hrubesch R, Paul C, Reichkendler M. Sportfähigkeit nach Verletzungen des Schultereckgelenks. Der Orthopäde. 2002.

- Ceccarelli E, Bondì R, Alviti F, Garofalo R, Miulli F, Padua R. Treatment of acute grade III acromioclavicular dislocation: a lack of evidence. J Orthop Traumatol. 2008 Jun;9(2):105–8.