Muscle Transfers at the Shoulder

On the whole, the results of muscle transfers to restore control of the scapula and to restore glenohumeral movement in adults are disappointing. Comtet, Herzberg, and Alnaasan[1] in an excellent review of biomechanics of the shoulder, girdle emphasized that proper control of the scapula is the basis for glenohumeral movement and that the upper fibers of the trapezius and the lower fibers of the serratus are essential for this. They recognize two muscular systems that can elevate the shoulder, the supraspinatus—infraspinatus complex and the deltoid. The deltoid muscle, however, cannot work if the rotator cuff is torn or is paralyzed, whereas functional abduction and external rotation are the rule if this system is intact even in the presence of paralysis of the deltoid. Narakas[2] introduced measurement of the scapulohumeral angle as an indication of function of the glenohumeral joint. The angle is least after rupture of the rotator cuff or injury to the suprascapular nerve, and it is equally poor when circumflex nerve injury is associated with either of these.

Role of Arthrodesis

Scapulothoracic arthrodesis3 is indicated in cases of irretrievable paralysis of the trapezius and serratus anterior, because there are no useful muscle transfers in this situation. Glenohumeral arthrodesis may prove necessary in irreparable paralysis of the deltoid, supraspinatus, and infraspinatus muscles.

I have found three muscles transfers to be of some value about the shoulder girdle. Transfer of the levator scapulae and of the rhomboids mitigates the disability from trapezius palsy.4-6 Transfer of the sternal part of the pectorahs major to the lower pole of the scapula restores some stability after paralysis of the serratus anterior.7 Transfer of the latissimus dorsi to the tendons of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus is useful in adults with paralysis of those muscles but some activity in the deltoid. Both Gilbert8 and Narakas9 emphasized that results of muscle transfers at the shoulder are a good deal better in children than in adults.

Normal power in the muscles to be transferred is an essential prerequisite for success. A painful stiff glenohumeral joint is a common complication of injuries to the spinal accessory and long thoracic nerves. It is common after prolonged immobilization of the shoulder girdle following muscle transfers. This must be recognized and treated.

Transfer of Latissimus Dorsi to Restore External Rotation at the Shoulder

Position of Patient

The patient lies prone.

Technique

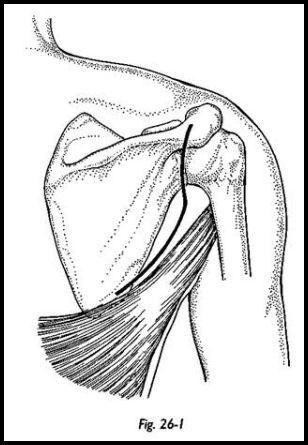

The incision starts behind the acromion and follows the posterior border of the deltoid to curve forward into the axilla overlying the conjoined insertion of the latissimus dorsi and teres major (Fig. 26-1). It is extended interiorly along the anterior margin of latissimus dorsi so that this can be mobilized.

The latissimus dorsi tendon is defined and separated from teres major. It is released from its insertion into the humerus, noting the position of radial and circumflex nerves. The muscle is mobilized, preserving the teres major and respecting the thoracodorsal pedicle, which lies anteriorly.

The posterior border of the deltoid is elevated to display the tendon of infraspinatus. The supraspinatus tendon is displayed by splitting the overlying fibers of the deltoid. The plane between the rotator cuff and overlying deltoid is developed.

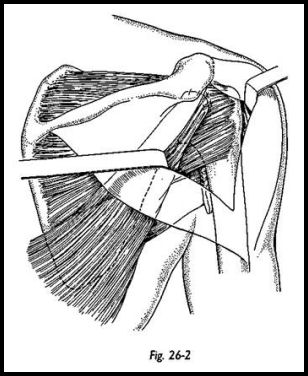

The latissimus dorsi is passed deep to the deltoid and interwoven into the tendons of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus (Fig. 26-2).

The fascia at the apex of the axilla is divided under direct vision so that a capacious tunnel allows passage of the tendon of pectoralis major into the axillary wound. The muscle glides smoothly over the ribs and over the origin of pectoralis major. The tendon is now sutured to the inferior pole of scapula with strong sutures, which pass through the bone to pick up the insertion of serratus anterior and the most inferior portion of subscapularis.

The wounds are closed over suction drain at each incision.

Postoperative Management

The arm is immobilized across the chest for 6 weeks. For 3 weeks thereafter, passive and active abduction to 40 degrees with external rotation to neutral are combined with gentle adduction. At 9 weeks, a more vigorous program is followed aiming to restore full range of abduction and external rotation by 12 -weeks from operation. At 12 weeks, a vigorous resisted work can begin.

Little is written about the outcome of this operation. Narakas10 found some improvement in five cases after various muscle transfers for paralysis of the serratus anterior. Our results in three cases of pectoralis minor transfer were unsatisfactory; there was some functional improvement in four cases of pectoralis major transfer. It seems that the transfer works best with the hand chest high or below. The time to achieve useful improvement is at least 1 year.

Transfer of the Levator Scapulae and Rhomboids for Paralysis of the Trapezius (Eden-Lange Operation)

Results from transfer of the levator scapulae and rhomboids for paralysis of the trapezius are far inferior to those following successful repair of the accessory nerve, and it is indicated only when the nerve is irreparable or when repair has failed.

Position of Patient

The patient is placed prone.

Technique

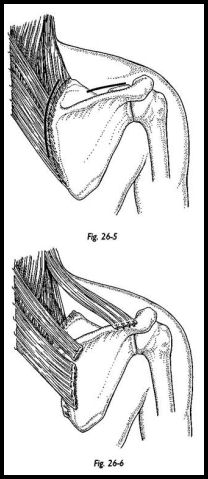

Preparation includes the whole of the upper limb, and the posterior chest wall to the spinous processes and the fold of the trapezius. There are two incisions. The first runs one finger's breadth parallel to the vertebral border of the scapula, detaching the paralyzed trapezius from the bone (Fig. 26-5). The levator scapulae and rhomboids are defined and mobilized. The dorsal scapular nerve must be respected during this dissection. The muscles are detached from the scapula together with an osteoperiosteal flap, respecting the insertion of serratus anterior, which lies deep.

The infraspinatus is elevated from the inferior fossa of the scapula. The scapula is now reduced so that its vertebral border lies parallel with the spinous processes, and the shoulder is abducted to 90 degrees (Fig. 26-6). The rhomboid minor and major are advanced between 3 and A cm lateral to the vertebral border of the scapula and secured to it by intraosseous suture.

The second incision is over the middle portion of the spine of scapula, detaching the trapezius. The levator scapulae is brought into this wound through a tunnel deep to the upper fibers of trapezius and sutured to the spine. The supraspinatus muscle and suprascapular nerve must be respected.

The reflected trapezius and, notably, infraspinatus are carefully reattached to the scapula. After wound closure, the patient is placed in an abduction spica with the shoulder secured at 90 degrees of abduction.

Postoperative Management

The plaster is removed at 6 weeks, and the patient remains in an abduction bolster for a further 3 weeks. Both passive and active movements of the glenohumeral joint are encouraged after removal of the plaster to prevent a secondary painful capsulitis. After 9 weeks, the patient wears a broad arm-supporting sling, and gentle active elevation and retraction of the scapula are permitted.

Bigliani, Perez-Sanz, and Wolfe6 reported substantial functional improvement with alleviation in pain in six of seven patients following this operation after a minimum follow-up of 2 years.

References

- Comtet J J, Herzberg G, Alnaasan I: Biomechanics of the shoulder and the scapulothoracic girdle, pp. 99-111. In Tubiana R (ed): The Hand. Vol. 4. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1993

- Narakas AO: Neurotization in the treatment of brachial plexus injuries, pp. 1329—58. In Gelberman RH (ed): Operative Nerve Repair and Reconstruction. JB Lippincott, Philadelphia, 1991

- Copeland SA, Howard RC: Thoracoscapular fusion for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 60:547-51, 1978

- Eden R: Zur Behandlung der Trapezius Lahmung mittelst Muskelplastik. Deutsche Zeitschrift Chir 184:387-97, 1924

- Lange M: Die Behandlung der Irreperalblem Trapezius Lahmung Lagenbecks. Arch Klin Chir 270:437-9, 1951

- Bigliani LU, Perez-Sanz JR, Wolfe IN: Treatment of trapezius paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 67:871-77, 1985

- Frey A, Sommelet J: La paralysie du grande dentele: resultat de traitement de 12 cas dont 9 operes et revue generale de la literature. Rev Cir Orthop 23:277, 1987

- Gilbert A: Obstetrical brachial plexus palsy, pp. 575-601. In Tubiana R (ed): The Hand. Vol. 4. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1993

- Narakas AO: Paralytic disorders of the shoulder girdle, pp. 112-25. In Tubiana R (ed): The Hand. Vol. 4. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1993