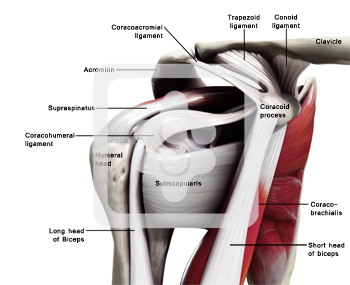

Glenohumeral capsule and ligaments normal anatomy

The advent of shoulder arthroscopy has led to a greater understanding of the shoulder capsule and ligaments, due to the closer visualisation it offers, of the intimate relationships between the ligaments and the parts they play in a larger complex. Arthroscopy has allowed the commonly recognised ligaments (superior, middle and inferior glenohumeral) to be seen as clearly defined bands, rather than as part of a large structure. The glenohumeral ligaments and capsule are always a source of great interest, as such a high proportion of shoulder disability is related to anterior dislocation or subluxation.

Fibrotendinous Cuff of the Capsule

The tendons of the rotator cuff fuse into one structure near their insertion onto the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus. Supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons join about 15 mm proximal to their insertions on the humerus and cannot be separated. Although there is an interval between the muscular potions of teres minor and the infraspinatus muscles, these muscles merge inseparably just proximal to the musculotendinous junction. Teres minor and subscapularis muscles have muscular insertions on the surgical neck of the humerus, which extended to approximately 2 cm below their tendinous attachments of the tubercles.

The tendons of the cuff are reinforced near their insertions on the tubercles of the humerus by fibrous structures with both superficial and deep locations.

Superficial - the superficial aspect of the tendons is covered by a thick sheet of fibrous tissue that lies beneath the deep layer of the subdeltoid bursa. This sheet is a fan-like posterolateral extension of a broad and thick fibrous band that extends from the lateral edge of the coracoid process over the supraspinatus and infarspinatus tendons to the humerus.

Deep - This band also sends fibres along the surface of the capsule into the

interval between the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons that attach

to both tubercles underneath both tendons.

Superior Glenohumeral ligament complex

Superior Glenohumeral Ligament

This ligament emerges from the upper pole of the glenoid labrum and has a few fibres deriving from the supraglenoid tubercle, ventral to the origin of the biceps tendon. Often the origin of the superior glenohumeral ligament partially merges with that of the middle glenohumeral ligament. It then runs parallel to the long tendon of the biceps muscle together with a small artery until laterally it starts running underneath the biceps tendon towards the lesser tubercle. The superior glenohumeral ligament inserts into the cartilaginous surface of the anterior margin of the bicipital groove and the upper part of the lesser tubercle into a dimple known as the fovea capitis humeri. In the majority of cases the superior glenohumeral ligament merges with the coracohumeral ligament either medially, at their mid-portions or laterally at the biceps pully.

The superior glenohumeral ligament lies above the subscapularis recess and makes up the superior margin of the foramen of Wiet-brecht. This ligament is often partially hidden by the long head of biceps when arthroscoping from the posterior portal (Figure 5.20).

Middle Glenohumeral Ligament

The middle glenohumeral ligament varies from a thin membranous structure (Figure 5.21) to a thick ligament, although its position is constant. The middle glenohumeral ligament can always be found crossing obliquely down across the subscapularis bursa and hiding all but the upper leading edge of the tendon from view (Figure 5.22).

Inferior glenohumeral ligament

The inferior glenohumeral ligament is the strongest and most important of the glenohumeral ligaments. The superior band is constant and can be seen passing downwards and outwards beneath the middle glenohumeral ligament (Figures 5.23 and 5.24). Often the inferior glenohumeral ligament can distinctly be seen as a prolongation of the anterior labrum (Figure 5.25). O'Brien and Warren[4] have looked in detail at the gross and microscopical nature of this ligament. They liken the ligament to a hammock, strung between the glenoid and the humeral head (Figure 5.26). The two ropes holding the hammock are the anterior superior band and, at the back, the posterior superior band. They have shown that the ligament thickens at these two points and that the configuration of the collagen bundles varies within the ligament, passing coronally between the glenoid and the humerus in the thickened superior bands, and sagittally in the substance of the ligament

between these bands. So it is the latter that makes up the infraglenoid

recess which, with the arm at the side, is a capacious space (Figures

5.27, 5.28 and 5.29).

Coracohumeral ligament

Coracoglenoid ligament

Posterosuperior glenohumeral ligament

Rotator Cable

Rotator Interval

Biceps Pulley

The arthroscope is now rotated within the infraglenoid recess to see the synovial reflection on the humeral neck. The arthroscope is now withdrawn gradually with rotation, for it is easy to withdraw too far at this point and exit the joint through the puncture point in the posterior capsule. As the arthroscope is rotated, so the posterior glenoid labrum can be seen (Figures 5.30, 5.31 and 5.32) and behind it the posterior gutter or synovial recess. As the arthroscope is rotated in the other direction, so the posterior surface of the humeral head is observed. At this point, it is important to look carefully at the synovial reflection, or so-called bare area of the humeral head (Figures 5.33 and 5.34) as it is easy for the inexpert arthro-scopist to mistake this for a Hill-Sachs lesion. The difference is that the bare area coalesces with the synovial reflection on the neck of the humerus, whereas a Hill-Sachs lesion has a ridge of bone or cartilage between it and the bare area. The bare area often has small pits or holes in it which can clearly be seen, and the junction between it and the articular surface of the head is more normal than the rounded-off fracture of a Hill-Sachs lesion. Further withdrawal and rotation brings the arthroscope back into the triangle between the long head of biceps, the humeral head and the glenoid.

Hook probe

As with arthroscopy of the knee, further tactile information can now be gleaned by the use of a hook probe. This is more difficult to insert than in the knee, and when learning it is often easier to start probing with a 14- or 12-gauge needle (Figure 5.35), or a Verres needle (Figure 5.36). The needle will cause less damage on insertion, and will also establish a flow through the joint. This clears any blood that may at this stage have started to obscure vision. If a hook probe is used it often helps to make a track with a sharp obturator and cannula from the anterior portal and then pass the hook down this track. Probing the glenoid labrum may show a Bankart lesion, or confirm one, if suspected. The ligaments can be probed in turn and then the long head of biceps and the superior cuff can be palpated.

On completion of the examination, the joint is thoroughly flushed through, the fluid removed from the shoulder, and the probe and arthroscope withdrawn.