Healthcare Outcomes

Bibhas Roy

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare outcomes are changes in health status, usually due to an intervention. Achieving good patient health outcomes is the fundamental purpose of health care. This can be applied for individuals as well as populations. Measuring this has become a multi‐million pound industry fuelled partly by increasing anxiety by society [1]. Measuring, reporting, and comparing outcomes is perhaps the most important step toward unlocking rapid outcome improvement and making good choices about reducing costs[2].Quality measurements are common in production processes, but this can translate poorly in the healthcare sector as links between actions and outcomes are much less direct[1], and there are other confounding factors which make comparison difficult. This makes risk adjustment or risk stratification an essential part of outcome measurements in healthcare[3]. There is evidence that a validated risk stratification model improves the accuracy of outcomes analysis.[4]

The concept of evidence based practice is based on evidence from studies and trials, outcomes however create a different way of thinking – a systematic analysis of outcomes can have many advantages by creating practice based evidence[5].

HISTORY

Possibly the earliest attempt at routinely measuring outcome in modern medicine was by Florence Nightingale in the 1850s. This was during the Crimean war and the outcome studied was death. However, one of her later publications regarding outcome[6] has an important lesson in it. Due to a statistical error, the mortality for London hospitals was thought to be about 90%; what had been calculated was death rates per occupied hospital bed, not mortality rates per the total number of hospitalised patients[7].Codman [8]introduced his end result idea in the early 1900s. He defined the idea as ‘The common sense notion that every hospital should follow every patient it treats, long enough to determine whether or not the treatment has been successful, and then to inquire, “If not, why not?” with a view to preventing similar failures in the future’. Unfortunately, this received little support from his peers; he was ostracized, and did not receive any appreciation in his lifetime.Attempts to standardize and evaluate medical care continued sporadically and Donabedian's classic paper[9] in 1966 described three areas; structure – the physical and staffing characteristics of caring for patients; process – the method of delivery; and outcome ‐ the results of care. Modern attempts at measuring healthcare outcomes are far from comprehenisve, but this is becoming increasingly important in clinical medicine as well as health economics.

OUTCOME MEASUREMENTS

Requirements for an Outcome measureTo be useful, an outcome measure needs to be valid, i.e. assessing what it is supposed to, and reliable, showing a minimum of error[10]. It also needs to be easy to administer, be sensitive

(able to identify what is being measured) and specific (able to identify false positives), as well as be responsive (able to measure change over time).

Process measures are the simplest to administer, but they often only show the outcome of administrative as opposed to clinical interventions (i.e. waiting times). As a basis of targets in healthcare, Pay‐for‐performance schemes that incentivise hospitals to focus on administrative process measures may be associated with decreased adherence to clinical processes[11]

Clinical outcomes are more difficult to develop and implement. However, patient reported outcomes are much easier to use than those requiring a clinical component such as information from a radiograph, details of an operation or assessment of range of movement[10]. It is the clinician reported measures that often complement the patient reported scores. Risk adjustment for patient reported scores can also be impossible without a clinician derived element. Specific instruments have been developed to try and minimize the potential for

1. Clinical outcomes

Clinician reported

This is the traditional ‘objective’ measure. The health care professional assesses the patient and the observations are usually recorded in numerical format. This allows comparison of before and after interventions as well as statistical analyses. One of the simplest examples of this kind of outcome is measuring the range of movement.Patient reportedThe ‘subjective’ measures where data is gathered by the patient in self‐administered questionnaires and scored by either clinicians or computers. Pain scores are the simplest scores of this kind.

The choice of instrument vary from generic e.g. EQ‐5D (EuroQol Group, 5 Dimensions) to condition specific e.g. Oxford shoulder instability score[12]. The generic tools are often used for health economics[13] and the more specific ones are more sensitive measures of specific diseases and interventions[14]. There are also intermediate scores that are suitable for a range of clinical situations i.e. the oxford shoulder score.

These are often validated against established clinician reported scores[15], and can be more sensitive and responsive[14].

Biologic predictors of results are not outcomes, but they must form the basis of risk adjustments when the clinical scores are used to compare providers of care.

There are scores that use aspects of clinician reported as well as patient reported measures to calculate an aggregate score. The Constant shoulder score is one such example.

Device generated

These can form the basis of both clinical as well as economic targets ‐ e.g. blood sugar levels, or blood pressure can be measured as a quality indicator. Usually these need to be used alongside other outcome measures.2. Process MeasuresProcess measures are measures of parts and activities within the healthcare system. These are simple measurements (e.g. waiting times), easy to implement, have limited requirements for risk adjustments, and provide feedback to clinicians as well as other stakeholder groups about what aspects of the system need improving. This data can be captured rapidly as the sample size required is usually smaller than those of clinical outcomes[16].

However there can be difficulty in specifying a suitable population for a process due to clinical reasons such as contraindications, health priorities etc. This also is a less valuable measure for both clinicians and patients as to be valid there needs to be a strong relationship between a process and a clinical measure, something that is rarely the case (Are patients who are seen quickly more likely to improve clinically than those who wait longer?).If process measures are not comprehensive they may well be misleading to the users[16]

3. Balancing outcomes

Balancing measures complete the measurement spectrum. These depend on the choice of the clinical and process measures and look at the system from a different angle, i.e is a short length of stay resulting in more readmissions.Balancing measures have to be an integral part of whole system measures to demonstrate valid outcome.

TIMING OF DATA CAPTURE

Sample

This is the classic way of capturing outcome data for research projects. Data is captured over a period of time for a specific sample size in order to translate it into meaningful information that can prove or refute a hypothesis. The sample size is predetermined by statistical methods that take into account the power of the study. Techniques such as randomized controls are used to minimize the effect of variations due unmeasured confounding factors. This is the basis of most of the ‘evidence’ that we rely upon for modern day ‘evidence based practice’. This is the gold standard for establishing cause & effect relationship.However, because of their design characteristics, findings from studies do not always reflect comparative effectiveness of treatments for all types of patients in routine practice. In spite of extensive quality control, treatment purity is difficult to maintain.Continuous

A pragmatic way to reduce uncertainty about effectiveness of treatments is the the concepyt of Practice based evidence. This has to capture comprehensive information about patient characteristics, processes, and outcomes to ascertain the contribution of individual processes to outcomes, controlling for patient differences. Practice‐Based Evidence for Clinical Practice Improvement requires analysis of this data for information.The data has to be transformed into information in real time for maximal efficacy, so the clinical team is aware of the process measures in real time. There is evidence that this approach can rapidly improve clinical care[17]

CONCLUSION

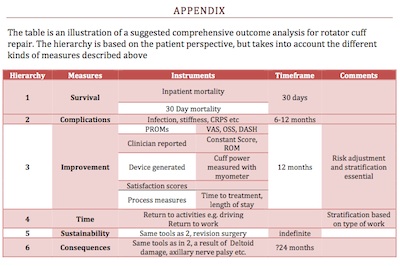

Measuring healthcare outcomes are now an essential part of healthcare. The different audience for this information range from the patients themselves to the healthcare policy makers. No single outcome measure is sufficient to comprehensively measure any aspect of healthcare, the various instruments above need to be considered by the multidisciplinary team including the clinician and the patient to obtain an appropriate ‘set’ of measures. The challenge is to have sufficient numbers of these, appropriately risk adjusted, that are then measured in real time with continuous feedback to all stakeholders. Appendix I describes a proposed group of comprehensive measurements for rotator cuff repair.APPENDIX

REFERENCE

1. Sheldon, T.A., The healthcare quality measurement industry: time to slow the juggernaut? Qual Saf Health Care, 2005. 14(1): p. 3‐4.2. Porter, M.E., What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 363(26): p. 2477‐81. 3. Orkin, F.K., Risk stratification, risk adjustment, and other risks. Anesthesiology. 113(5): p.1001‐3. 4. Jacobs, J.P., et al., Stratification of complexity improves the utility and accuracy of

outcomes analysis in a MultiInstitutional Congenital Heart Surgery Database: Application of the Risk Adjustment in Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS1) and Aristotle Systems in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Congenital Heart Surgery Database. Pediatr Cardiol, 2009. 30(8): p. 1117‐30.

5. Horn, S.D. and J. Gassaway, Practicebased evidence study design for comparative effectiveness research. Med Care, 2007. 45(10 Supl 2): p. S50‐7.

6. Nightingale, F., Notes on hospitals (3rd ed.). . Editor. 1863, Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green.: London.

7. Iezzoni, L.I., 100 apples divided by 15 red herrings: a cautionary tale from the mid19th century on comparing hospital mortality rates. Ann Intern Med, 1996. 124(12): p. 1079‐ 85.

8. EA, C., The Shoulder: Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon and Other Lesions In or About the Subacromial Bursa. 1934, Boston: Thomas Todd Co.

9. Donabedian, A., Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q, 1966. 44(3): p. Suppl:166‐206.

10. Pynsent, P.B., Choosing an outcome measure. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2001. 83(6): p. 792‐4. 11. Glickman, S.W., et al., Alternative payforperformance scoring methods: implications for quality improvement and patient outcomes. Med Care, 2009. 47(10): p. 1062‐8.

12. Dawson, J., R. Fitzpatrick, and A. Carr, The assessment of shoulder instability. The development and validation of a questionnaire. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1999. 81(3): p. 420‐ 6.

13. Preedy, V.R. and R.R. Watson, Handbook of disease burdens and quality of life measures, New York: Springer. 6 v. (lx, 4447 p.).

14. Dawson, J., et al., Comparison of clinical and patientbased measures to assess medium term outcomes following shoulder surgery for disorders of the rotator cuff. Arthritis Rheum, 2002. 47(5): p. 513‐9.

15. Parsons, N.R., et al., A comparison of Harris and Oxford hip scores for assessing outcome after resurfacing arthroplasty of the hip: can the patient tell us everything we need to know. Hip Int. 20(4): p. 453‐9.

16. Rubin, H.R., P. Pronovost, and G.B. Diette, The advantages and disadvantages of process based measures of health care quality. Int J Qual Health Care, 2001. 13(6): p. 469‐74.

17. Beaulieu, P.A., et al., Transforming administrative data into realtime information in the Department of Surgery. Qual Saf Health Care. 19(5): p. 399‐404.

Courtesy of www.shouldersurgery.info