Posterior Shoulder Instability

Lennard Funk

Introduction

This presentation will discuss some current concepts in posterior unidirectional instability of the shoulder. I will not be covering acute or chronic dislocations, or multidirectional instability.

History

Hippocrates first described reduction for posterior dislocation of the shoulder. He described taking the forearm behind the back into internal rotation, flexing the elbow and pushing in the shoulder from behind.Sir Astley Cooper was the first to describe a posterior dislocation in a patient with a seizure and Malgaigne was the first to describe a series of 37 patients with Posterior Instability in 1855 – before the advent of radiology.

During the 20th century the results of surgical treatment of posterior shoulder instability have been as varied as the techniques designed to correct it. In 1984 Hawkins et al. reported a 50% failure rate after a variety of different posterior stabilization procedures for recurrent instability of the shoulder. Tibone and Ting reported failure in 40% of athletes treated with staple capsulorrhaphy. Until recently the pathomechanics and role of surgery for pure posterior instability have been poorly understood.

|

|

|

|

Hippocrates |

Malgaine's sketches of Posterior Dislocation |

Aetiology

It is simplest to divide posterior instability into Traumatic and Atraumatic origins. Traumatic instability typically follows a distinct history of dislocation or subluxation, sustained during a significant injury.

Patients with atraumatic instability often have no history of true dislocations, but on probing there often is a history of minor trauma or repetitive microtrauma (sports). This is usually associated with capsular laxity and/or muscle patterning abnormalities.

Classification

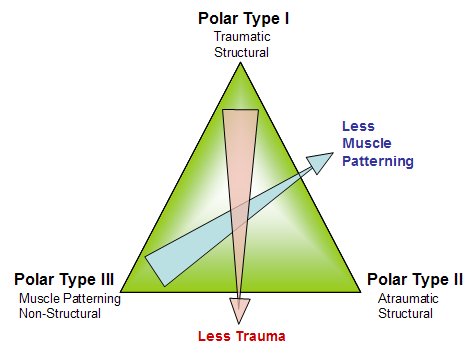

We use the Stanmore classification to describe and guide our management of patients with instability. It takes into account the marked overlap between traumatic and atraumatic dislocators and also the fact that these do change over time. For more details read: Lewis, Kitamura & Bayley in Current Orthopaedics. 18:97-108. 2004.

|

|

|

Stanmore Classification (Bayley Triangle) |

Posterior Restraints

The posterior restraints to posterior translation of the humeral head are:

1. Glenoid: version and shape. Abnormalities in the glenoid shape and version has been described as more common in patients with atraumatic posterior instability. (Weishaupt,2000). The greater the retroversion of the glenoid the more prone it is to posterior dislocation. Generally with a retroversion of greater then 20 degrees one should consider a glenoid osteotomy. However, even with CT it is difficult to accurately measure glenoid version, as with rotation fo the scapula the axial plane varies and thus the measured version from these cuts (Bokor, 1999)

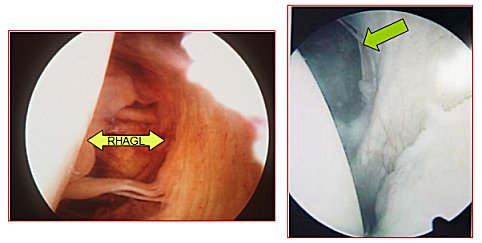

2. Capsule: IGHL plays a significant role at the extremes of internal humeral rotation. Unlike the anterior structures, the posterior capsule is relatively thin with less clearly defined ligamentous components, especially superiorly above the equator. Although O'Brien et al. have described a posterior thickening or band of the IGHLC, other investigators have found its presence to be inconsistent. This may in part reflect variation in sampling depending on glenohumeral positioning. This region has, however, been shown to be the primary capsuloligamentous restraint to posterior translation at higher degrees of elevation and internal rotation. Transection studies have also demonstrated that if, in isolation, the posterior capsule was completely incised, the glenohumeral joint did not dislocate posteriorly (Harryman, 1992). For dislocation to occur in the flexed, adducted, and internally rotated shoulder, in addition to the posterior capsule, the rotator cuff interval had to be incised as well. The posterior capsule may be torn in the midcapsule or at it’s humeral attachment = Reverse Humeral Avulsion Glenohumeral Ligament (RHAGL).

|

|

|

Arthroscopic images showing a RHAGL on the left and a mid-capsular tear on the right |

3. Rotator Interval: Plays an important role with the humerus in neutral rotation. Harryman et al. (Harryman, 1992) have also shown the importance of the rotator cuff interval tissue in posterior and inferior translation. Incision of the rotator interval capsule increased posterior translation by 50% and inferior translations by 100%, suggesting resultant overlap in magnitude and direction of the various capsular regions to the overall instability pattern (Harryman, 1992).

4. Labrum: Usually torn in Traumatic dislocations, with the formation of a posterior Bankart lesion. The importance of the posterior labrum in posterior instability has been neglected in the past. Since the advent of arthroscopy posterior labral lesions have been more commonly found and treated. Antoniou & Harryman (2001) have described the significance of reconstructing the glenolabral depth with a capsulolabral repair in establishing structural stability (). Recent posterior labral lesions described: POPSLA lesion – Posterior Periosteal Sleeve Labral Avulsion (Yu et al. Skel Radiol. 2002. 31:396-9) Kim’s Lesion – Incomplete & concealed avulsion posteroinferior labrum (Kim, 2001).

|

|

|

Posteroir Labral Tear (Reverse Bankart tear) |

5. Subscapularis: Blasier et al identified the subscapularis as being the muscle providing the greatest resistance to posterior subluxation of the humerus (Blasier RB, Soslowsky LJ, Malicky DM, et al: Posterior glenohumeral subluxation: Active and passive stabilization in a biomechanical model. J Bone Joint Surg Am 79:433-440, 1997)

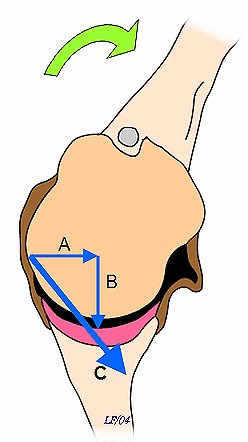

6. Reduced external rotation: Limited external rotation, due tight anterior structures, is seen in athletes. This is an obligate translation. Capsular tensioning produces a vector, which can be resolved into a horizontal and a vertical component. The vertical component is responsible for compression of the humeral head into the glenoid and therefore for increased stability. The horizontal component acts to push the humeral head off the glenoid. The net humeral motion is posterior translation of the humeral head (see diagram).

|

|

| Capsular tensioning produces a vector (A), which can be resolved into a horizontal component (B) and a vertical component (C). The vertical component is responsible for compression of the humeral head into the glenoid and therefore for increased stability. The horizontal component acts to push the humeral head off the glenoid. Note direction of humeral motion (arrow). |

Mechanism of Injury

Post dislocation is much less common than anterior and may often be missed, as mentioned above. Athletes, such as eight lifters, throwers, racket sport athletes, rugby players, and swimmers at higher risk. Many of these athletes have inherently lax shoulders, which is an advantage for their sports, but also makes them prone to instability. They receive repetitive trauma to their shoulders which can lead to chronic instability.

History

These patients often don’t present with a typical history of true dislocations, but rather symptoms of posterior joint pain and/or clicking. The exact positions of the shoulder causing the pain and/or click should be described. Often this the pain occurs when loading the flexed and internally rotated shoulder. This can be confused with subacromial impingement; therefore careful clinical examination is essential.

Clinical Examination

The clinical examination is the most important part of the diagnostic process. It is beyond the scope of this presentation to discuss the detailed examination, but it should include all of the following:

- Core Stability

- Muscle Patterning

- Laxity (both the shoulder and general)

- Stability

- Proprioception

- Psychology

This is ideally done by a multidisciplinary team, comprising the surgeon, physiotherapist and occupational therapist.

Psychological causes are extremely rare and it is a diagnosis of exclusion. A voluntary dislocator does not equate with a psychological cause.

The table below shows a review of some of the clinical tests for posterior instability:

Investigations

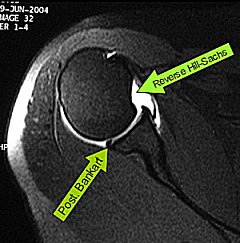

Usually include radiographs (AP and axillary views) and MR Arthrogram in all patients with suspected posterior instability. Sometimes a CT scan for bony lesions, glenoid deficiency and version may be required. Functional EMG is also helpful for complex muscle patterning disorders. Examination under anaesthesia and arthroscopy aids the diagnosis, although one should have most of the information before this.

|

Axillary x-ray showing large reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (click on image for more) |

|

Posterior Bony Bankart lesion (click on image for more) |

|

MR Arthrogram showing soft tissue Bankart and reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (click on image for more) |

Decision Making

If the primary abnormality is musle patterning and proprioceptive problems the physiotherapy is the main treatment. It is essential that this is undertaken by a therapist trained and experienced in dealing with shoulder instability, as the rehabilitation can be long and arduous. There needs to be a close relationship between the therapist and the surgeon, to ensure that if surgery is required this is done as part of the full rehab program and done timely in accordance with the rehab.

If the primary abnormality is found to be structural (eg. Bankart lesion, bony lesion or capsular injury) then surgery is often required early and the rehab follows accordingly.

Surgery for Posterior Instability

The surgery for posterior instability depends on the injuries. It is essential to identify the pathology and treat accordingly. No single operation applies to all patients with posterior instability.

1. Soft Tissue Injuries

Soft tissue injuries are much more common than bony. Most of my procedures for posterior instability have been soft tissue reconstructions. These include:

- Posterior Capsulolabral repair: repair of the soft tissue posterior bony Bankart lesion, often combined with a capsular shift. See 'Authors Preference' below.

- Capsular Shift: A posterior capsular shift may be required for a hyperlax posterior capsule in the abscence of a labral injury

- Capsular Shrinkage: This is required as part of the rehabilitative programme for patients with laxity and proprioceptive instability (Polar II/III). For more details and arthroscopic video see Capsular Shrinkage

2. Bony Injuries

Bony abnormalities are rare, but should always be considered, especially in patients with failed soft tissue surgery and no muscle patterning or proprioceptive problems. These procedures include:

- Glenoid Osteotomy: As mentioned above, a glenoid retroversion of above 20 degrees should be considered for glenoid osteotomy.

- Subscapularis Transfer: The original McLaughlin procedure involved transfer of the subscapularis tendon from the lesser tuberosity to the reverse Hill-Sachs defect, however Neers's modification has become more popular. This involves transfer of the lesser tuberosity along with subscapularis. Healing is improved and the defect can be filled.

- Posterior Bone Block: This procedure is only considered in extreme cases as a bony block to posterior translation of the humeral head. Failure rates are reported to be high.

Authors Preference

As most of the cases I have treated have been sports people with capsulolabral injuries, I prefer to surgically manage the vast majority of patients with arthroscopic repair. These are all patients with true structural lesions. Thise without true structural lesions are managed with arthroscopic thermal capsular shrinkage and intensive specialist physiotherapy.

The advantages of arthroscopic repair include:

- Lower morbidity

- The ability to easily assess the entire joint and treat associated pathology, such as SLAP lesions, Rotator Interval lesions and anterior labral injuries.

- Easier revision, if required later on

The reported success rates are over 85% at 2 years, as long as the correct diagnosis is made and appropriate rehab applied. The key elements of successfully correcting posterior instability by arthroscopic means include increasing the glenohumeral stability ratio by restoring the glenolabral concavity, reducing the capsular redundancy to reset capsular tension for proprioceptive feedback, and rehabilitating scapulohumeral and scapulothoracic musculature (Antoniou, 2001).

Click on the Cases below to see some case of Arthroscopic Repairs:

Post-operative Rehabilitation

The details of the post-op rehabilitation is in the Therapists Section .

Conclusion

Unidirectional posterior shoulder instability is much less common than anterior instability, however it should be strongly suspected in those high risk group of athletes with posteroir shoulder pain and/or clicking. The treatment involves a combination of skilled therapy and surgery for optimal outcome.

References:

- Lewis, Kitamura & Bayley. Current Orthopaedics. 18:97-108. 2004.

- Weishaupt D. Posterior glenoid rim deficiency in recurrent (atraumatic) posterior shoulder instability. Skeletal Radiol. 01-APR-2000; 29(4): 204-10.

- Variability of measurement of glenoid version on computed tomography scan. Bokor DJ - J Shoulder Elbow Surg - 01-NOV-1999; 8(6): 595-8

- Harryman DT, Sidles JA, Harris SL, et al: The role of the rotator interval capsule in passive motion and stability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am 74:53-66, 1992.

- Kim et al. Arthroscopy. 2004 Sep;20(7):712-20

- Antoniou J, Harryman DT. Orthop Clin North Am. 01-JUL-2001; 32(3): 463-73, ix.

Lennard Funk

![]() top

top